The different types of ZK-EVMs

2022 Aug 04

See all posts

The different types of ZK-EVMs

Special thanks to the PSE, Polygon Hermez, Zksync, Scroll, Matter Labs and Starkware teams for discussion and review.

There have been many "ZK-EVM" projects making flashy announcements recently. Polygon open-sourced their ZK-EVM project, ZKSync released their plans for ZKSync 2.0, and the relative newcomer Scroll announced their ZK-EVM recently. There is also the ongoing effort from the Privacy and Scaling Explorations team, Nicolas Liochon et al's team, an alpha compiler from the EVM to Starkware's ZK-friendly language Cairo, and certainly at least a few others I have missed.

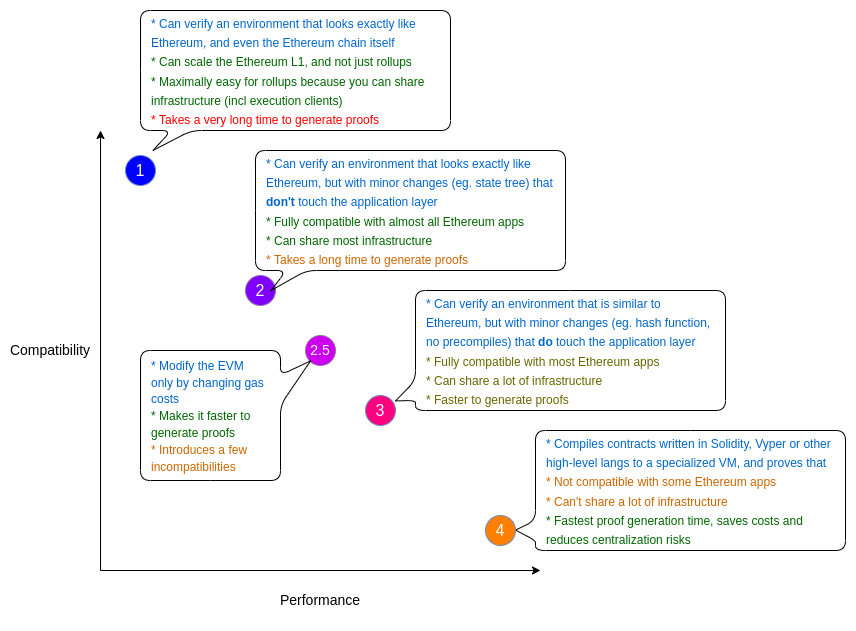

The core goal of all of these projects is the same: to use ZK-SNARK technology to make cryptographic proofs of execution of Ethereum-like transactions, either to make it much easier to verify the Ethereum chain itself or to build ZK-rollups that are (close to) equivalent to what Ethereum provides but are much more scalable. But there are subtle differences between these projects, and what tradeoffs they are making between practicality and speed. This post will attempt to describe a taxonomy of different "types" of EVM equivalence, and what are the benefits and costs of trying to achieve each type.

Type 1 (fully Ethereum-equivalent)

Type 1 ZK-EVMs strive to be fully and uncompromisingly Ethereum-equivalent. They do not change any part of the Ethereum system to make it easier to generate proofs. They do not replace hashes, state trees, transaction trees, precompiles or any other in-consensus logic, no matter how peripheral.

Advantage: perfect compatibility

The goal is to be able to verify Ethereum blocks as they are today - or at least, verify the execution-layer side (so, beacon chain consensus logic is not included, but all the transaction execution and smart contract and account logic is included).

Type 1 ZK-EVMs are what we ultimately need make the Ethereum layer 1 itself more scalable. In the long term, modifications to Ethereum tested out in Type 2 or Type 3 ZK-EVMs might be introduced into Ethereum proper, but such a re-architecting comes with its own complexities.

Type 1 ZK-EVMs are also ideal for rollups, because they allow rollups to re-use a lot of infrastructure. For example, Ethereum execution clients can be used as-is to generate and process rollup blocks (or at least, they can be once withdrawals are implemented and that functionality can be re-used to support ETH being deposited into the rollup), so tooling such as block explorers, block production, etc is very easy to re-use.

Disadvantage: prover time

Ethereum was not originally designed around ZK-friendliness, so there are many parts of the Ethereum protocol that take a large amount of computation to ZK-prove. Type 1 aims to replicate Ethereum exactly, and so it has no way of mitigating these inefficiencies. At present, proofs for Ethereum blocks take many hours to produce. This can be mitigated either by clever engineering to massively parallelize the prover or in the longer term by ZK-SNARK ASICs.

Who's building it?

The Privacy and Scaling Explorations team ZK-EVM effort is building a Type 1 ZK-EVM.

Type 2 (fully EVM-equivalent)

Type 2 ZK-EVMs strive to be exactly EVM-equivalent, but not quite Ethereum-equivalent. That is, they look exactly like Ethereum "from within", but they have some differences on the outside, particularly in data structures like the block structure and state tree.

The goal is to be fully compatible with existing applications, but make some minor modifications to Ethereum to make development easier and to make proof generation faster.

Advantage: perfect equivalence at the VM level

Type 2 ZK-EVMs make changes to data structures that hold things like the Ethereum state. Fortunately, these are structures that the EVM itself cannot access directly, and so applications that work on Ethereum would almost always still work on a Type 2 ZK-EVM rollup. You would not be able to use Ethereum execution clients as-is, but you could use them with some modifications, and you would still be able to use EVM debugging tools and most other developer infrastructure.

There are a small number of exceptions. One incompatibility arises for applications that verify Merkle proofs of historical Ethereum blocks to verify claims about historical transactions, receipts or state (eg. bridges sometimes do this). A ZK-EVM that replaces Keccak with a different hash function would break these proofs. However, I usually recommend against building applications this way anyway, because future Ethereum changes (eg. Verkle trees) will break such applications even on Ethereum itself. A better alternative would be for Ethereum itself to add future-proof history access precompiles.

Disadvantage: improved but still slow prover time

Type 2 ZK-EVMs provide faster prover times than Type 1 mainly by removing parts of the Ethereum stack that rely on needlessly complicated and ZK-unfriendly cryptography. Particularly, they might change Ethereum's Keccak and RLP-based Merkle Patricia tree and perhaps the block and receipt structures. Type 2 ZK-EVMs might instead use a different hash function, eg. Poseidon. Another natural modification is modifying the state tree to store the code hash and keccak, removing the need to verify hashes to process the EXTCODEHASH and EXTCODECOPY opcodes.

These modifications significantly improve prover times, but they do not solve every problem. The slowness from having to prove the EVM as-is, with all of the inefficiencies and ZK-unfriendliness inherent to the EVM, still remains. One simple example of this is memory: because an MLOAD can read any 32 bytes, including "unaligned" chunks (where the start and end are not multiples of 32), an MLOAD can't simply be interpreted as reading one chunk; rather, it might require reading two consecutive chunks and performing bit operations to combine the result.

Who's building it?

Scroll's ZK-EVM project is building toward a Type 2 ZK-EVM, as is Polygon Hermez. That said, neither project is quite there yet; in particular, a lot of the more complicated precompiles have not yet been implemented. Hence, at the moment both projects are better considered Type 3.

Type 2.5 (EVM-equivalent, except for gas costs)

One way to significantly improve worst-case prover times is to greatly increase the gas costs of specific operations in the EVM that are very difficult to ZK-prove. This might involve precompiles, the KECCAK opcode, and possibly specific patterns of calling contracts or accessing memory or storage or reverting.

Changing gas costs may reduce developer tooling compatibility and break a few applications, but it's generally considered less risky than "deeper" EVM changes. Developers should take care to not require more gas in a transaction than fits into a block, to never make calls with hard-coded amounts of gas (this has already been standard advice for developers for a long time).

An alternative way to manage resource constraints is to simply set hard limits on the number of times each operation can be called. This is easier to implement in circuits, but plays much less nicely with EVM security assumptions. I would call this approach Type 3 rather than Type 2.5.

Type 3 (almost EVM-equivalent)

Type 3 ZK-EVMs are almost EVM-equivalent, but make a few sacrifices to exact equivalence to further improve prover times and make the EVM easier to develop.

Advantage: easier to build, and faster prover times

Type 3 ZK-EVMs might remove a few features that are exceptionally hard to implement in a ZK-EVM implementation. Precompiles are often at the top of the list here;. Additionally, Type 3 ZK-EVMs sometimes also have minor differences in how they treat contract code, memory or stack.

Disadvantage: more incompatibility

The goal of a Type 3 ZK-EVM is to be compatible with most applications, and require only minimal re-writing for the rest. That said, there will be some applications that would need to be rewritten either because they use pre-compiles that the Type 3 ZK-EVM removes or because of subtle dependencies on edge cases that the VMs treat differently.

Who's building it?

Scroll and Polygon are both Type 3 in their current forms, though they're expected to improve compatibility over time. Polygon has a unique design where they are ZK-verifying their own internal language called zkASM, and they interpret ZK-EVM code using the zkASM implementation. Despite this implementation detail, I would still call this a genuine Type 3 ZK-EVM; it can still verify EVM code, it just uses some different internal logic to do it.

Today, no ZK-EVM team wants to be a Type 3; Type 3 is simply a transitional stage until the complicated work of adding precompiles is finished and the project can move to Type 2.5. In the future, however, Type 1 or Type 2 ZK-EVMs may become Type 3 ZK-EVMs voluntarily, by adding in new ZK-SNARK-friendly precompiles that provide functionality for developers with low prover times and gas costs.

Type 4 (high-level-language equivalent)

A Type 4 system works by taking smart contract source code written in a high-level language (eg. Solidity, Vyper, or some intermediate that both compile to) and compiling that to some language that is explicitly designed to be ZK-SNARK-friendly.

Advantage: very fast prover times

There is a lot of overhead that you can avoid by not ZK-proving all the different parts of each EVM execution step, and starting from the higher-level code directly.

I'm only describing this advantage with one sentence in this post (compared to a big bullet point list below for compatibility-related disadvantages), but that should not be interpreted as a value judgement! Compiling from high-level languages directly really can greatly reduce costs and help decentralization by making it easier to be a prover.

Disadvantage: more incompatibility

A "normal" application written in Vyper or Solidity can be compiled down and it would "just work", but there are some important ways in which very many applications are not "normal":

- Contracts may not have the same addresses in a Type 4 system as they do in the EVM, because CREATE2 contract addresses depend on the exact bytecode. This breaks applications that rely on not-yet-deployed "counterfactual contracts", ERC-4337 wallets, EIP-2470 singletons and many other applications.

- Handwritten EVM bytecode is more difficult to use. Many applications use handwritten EVM bytecode in some parts for efficiency. Type 4 systems may not support it, though there are ways to implement limited EVM bytecode support to satisfy these use cases without going through the effort of becoming a full-on Type 3 ZK-EVM.

- Lots of debugging infrastructure cannot be carried over, because such infrastructure runs over the EVM bytecode. That said, this disadvantage is mitigated by the greater access to debugging infrastructure from "traditional" high-level or intermediate languages (eg. LLVM).

Developers should be mindful of these issues.

Who's building it?

ZKSync is a Type 4 system, though it may add compatibility for EVM bytecode over time. Nethermind's Warp project is building a compiler from Solidity to Starkware's Cairo, which will turn StarkNet into a de-facto Type 4 system.

The future of ZK-EVM types

The types are not unambiguously "better" or "worse" than other types. Rather, they are different points on the tradeoff space: lower-numbered types are more compatible with existing infrastructure but slower, and higher-numbered types are less compatible with existing infrastructure but faster. In general, it's healthy for the space that all of these types are being explored.

Additionally, ZK-EVM projects can easily start at higher-numbered types and jump to lower-numbered types (or vice versa) over time. For example:

- A ZK-EVM could start as Type 3, deciding not to include some features that are especially hard to ZK-prove. Later, they can add those features over time, and move to Type 2.

- A ZK-EVM could start as Type 2, and later become a hybrid Type 2 / Type 1 ZK-EVM, by providing the possibility of operating either in full Ethereum compatibility mode or with a modified state tree that can be proven faster. Scroll is considering moving in this direction.

- What starts off as a Type 4 system could become Type 3 over time by adding the ability to process EVM code later on (though developers would still be encouraged to compile direct from high-level languages to reduce fees and prover times)

- A Type 2 or Type 3 ZK-EVM can become a Type 1 ZK-EVM if Ethereum itself adopts its modifications in an effort to become more ZK-friendly.

- A Type 1 or Type 2 ZK-EVM can become a Type 3 ZK-EVM by adding a precompile for verifying code in a very ZK-SNARK-friendly language. This would give developers a choice between Ethereum compatibility and speed. This would be Type 3, because it breaks perfect EVM equivalence, but for practical intents and purposes it would have a lot of the benefits of Type 1 and 2. The main downside might be that some developer tooling would not understand the ZK-EVM's custom precompiles, though this could be fixed: developer tools could add universal precompile support by supporting a config format that includes an EVM code equivalent implementation of the precompile.

Personally, my hope is that everything becomes Type 1 over time, through a combination of improvements in ZK-EVMs and improvements to Ethereum itself to make it more ZK-SNARK-friendly. In such a future, we would have multiple ZK-EVM implementations which could be used both for ZK rollups and to verify the Ethereum chain itself. Theoretically, there is no need for Ethereum to standardize on a single ZK-EVM implementation for L1 use; different clients could use different proofs, so we continue to benefit from code redundancy.

However, it is going to take quite some time until we get to such a future. In the meantime, we are going to see a lot of innovation in the different paths to scaling Ethereum and Ethereum-based ZK-rollups.

The different types of ZK-EVMs

2022 Aug 04 See all postsSpecial thanks to the PSE, Polygon Hermez, Zksync, Scroll, Matter Labs and Starkware teams for discussion and review.

There have been many "ZK-EVM" projects making flashy announcements recently. Polygon open-sourced their ZK-EVM project, ZKSync released their plans for ZKSync 2.0, and the relative newcomer Scroll announced their ZK-EVM recently. There is also the ongoing effort from the Privacy and Scaling Explorations team, Nicolas Liochon et al's team, an alpha compiler from the EVM to Starkware's ZK-friendly language Cairo, and certainly at least a few others I have missed.

The core goal of all of these projects is the same: to use ZK-SNARK technology to make cryptographic proofs of execution of Ethereum-like transactions, either to make it much easier to verify the Ethereum chain itself or to build ZK-rollups that are (close to) equivalent to what Ethereum provides but are much more scalable. But there are subtle differences between these projects, and what tradeoffs they are making between practicality and speed. This post will attempt to describe a taxonomy of different "types" of EVM equivalence, and what are the benefits and costs of trying to achieve each type.

Overview (in chart form)

Type 1 (fully Ethereum-equivalent)

Type 1 ZK-EVMs strive to be fully and uncompromisingly Ethereum-equivalent. They do not change any part of the Ethereum system to make it easier to generate proofs. They do not replace hashes, state trees, transaction trees, precompiles or any other in-consensus logic, no matter how peripheral.

Advantage: perfect compatibility

The goal is to be able to verify Ethereum blocks as they are today - or at least, verify the execution-layer side (so, beacon chain consensus logic is not included, but all the transaction execution and smart contract and account logic is included).

Type 1 ZK-EVMs are what we ultimately need make the Ethereum layer 1 itself more scalable. In the long term, modifications to Ethereum tested out in Type 2 or Type 3 ZK-EVMs might be introduced into Ethereum proper, but such a re-architecting comes with its own complexities.

Type 1 ZK-EVMs are also ideal for rollups, because they allow rollups to re-use a lot of infrastructure. For example, Ethereum execution clients can be used as-is to generate and process rollup blocks (or at least, they can be once withdrawals are implemented and that functionality can be re-used to support ETH being deposited into the rollup), so tooling such as block explorers, block production, etc is very easy to re-use.

Disadvantage: prover time

Ethereum was not originally designed around ZK-friendliness, so there are many parts of the Ethereum protocol that take a large amount of computation to ZK-prove. Type 1 aims to replicate Ethereum exactly, and so it has no way of mitigating these inefficiencies. At present, proofs for Ethereum blocks take many hours to produce. This can be mitigated either by clever engineering to massively parallelize the prover or in the longer term by ZK-SNARK ASICs.

Who's building it?

The Privacy and Scaling Explorations team ZK-EVM effort is building a Type 1 ZK-EVM.

Type 2 (fully EVM-equivalent)

Type 2 ZK-EVMs strive to be exactly EVM-equivalent, but not quite Ethereum-equivalent. That is, they look exactly like Ethereum "from within", but they have some differences on the outside, particularly in data structures like the block structure and state tree.

The goal is to be fully compatible with existing applications, but make some minor modifications to Ethereum to make development easier and to make proof generation faster.

Advantage: perfect equivalence at the VM level

Type 2 ZK-EVMs make changes to data structures that hold things like the Ethereum state. Fortunately, these are structures that the EVM itself cannot access directly, and so applications that work on Ethereum would almost always still work on a Type 2 ZK-EVM rollup. You would not be able to use Ethereum execution clients as-is, but you could use them with some modifications, and you would still be able to use EVM debugging tools and most other developer infrastructure.

There are a small number of exceptions. One incompatibility arises for applications that verify Merkle proofs of historical Ethereum blocks to verify claims about historical transactions, receipts or state (eg. bridges sometimes do this). A ZK-EVM that replaces Keccak with a different hash function would break these proofs. However, I usually recommend against building applications this way anyway, because future Ethereum changes (eg. Verkle trees) will break such applications even on Ethereum itself. A better alternative would be for Ethereum itself to add future-proof history access precompiles.

Disadvantage: improved but still slow prover time

Type 2 ZK-EVMs provide faster prover times than Type 1 mainly by removing parts of the Ethereum stack that rely on needlessly complicated and ZK-unfriendly cryptography. Particularly, they might change Ethereum's Keccak and RLP-based Merkle Patricia tree and perhaps the block and receipt structures. Type 2 ZK-EVMs might instead use a different hash function, eg. Poseidon. Another natural modification is modifying the state tree to store the code hash and keccak, removing the need to verify hashes to process the

EXTCODEHASHandEXTCODECOPYopcodes.These modifications significantly improve prover times, but they do not solve every problem. The slowness from having to prove the EVM as-is, with all of the inefficiencies and ZK-unfriendliness inherent to the EVM, still remains. One simple example of this is memory: because an

MLOADcan read any 32 bytes, including "unaligned" chunks (where the start and end are not multiples of 32), an MLOAD can't simply be interpreted as reading one chunk; rather, it might require reading two consecutive chunks and performing bit operations to combine the result.Who's building it?

Scroll's ZK-EVM project is building toward a Type 2 ZK-EVM, as is Polygon Hermez. That said, neither project is quite there yet; in particular, a lot of the more complicated precompiles have not yet been implemented. Hence, at the moment both projects are better considered Type 3.

Type 2.5 (EVM-equivalent, except for gas costs)

One way to significantly improve worst-case prover times is to greatly increase the gas costs of specific operations in the EVM that are very difficult to ZK-prove. This might involve precompiles, the KECCAK opcode, and possibly specific patterns of calling contracts or accessing memory or storage or reverting.

Changing gas costs may reduce developer tooling compatibility and break a few applications, but it's generally considered less risky than "deeper" EVM changes. Developers should take care to not require more gas in a transaction than fits into a block, to never make calls with hard-coded amounts of gas (this has already been standard advice for developers for a long time).

An alternative way to manage resource constraints is to simply set hard limits on the number of times each operation can be called. This is easier to implement in circuits, but plays much less nicely with EVM security assumptions. I would call this approach Type 3 rather than Type 2.5.

Type 3 (almost EVM-equivalent)

Type 3 ZK-EVMs are almost EVM-equivalent, but make a few sacrifices to exact equivalence to further improve prover times and make the EVM easier to develop.

Advantage: easier to build, and faster prover times

Type 3 ZK-EVMs might remove a few features that are exceptionally hard to implement in a ZK-EVM implementation. Precompiles are often at the top of the list here;. Additionally, Type 3 ZK-EVMs sometimes also have minor differences in how they treat contract code, memory or stack.

Disadvantage: more incompatibility

The goal of a Type 3 ZK-EVM is to be compatible with most applications, and require only minimal re-writing for the rest. That said, there will be some applications that would need to be rewritten either because they use pre-compiles that the Type 3 ZK-EVM removes or because of subtle dependencies on edge cases that the VMs treat differently.

Who's building it?

Scroll and Polygon are both Type 3 in their current forms, though they're expected to improve compatibility over time. Polygon has a unique design where they are ZK-verifying their own internal language called zkASM, and they interpret ZK-EVM code using the zkASM implementation. Despite this implementation detail, I would still call this a genuine Type 3 ZK-EVM; it can still verify EVM code, it just uses some different internal logic to do it.

Today, no ZK-EVM team wants to be a Type 3; Type 3 is simply a transitional stage until the complicated work of adding precompiles is finished and the project can move to Type 2.5. In the future, however, Type 1 or Type 2 ZK-EVMs may become Type 3 ZK-EVMs voluntarily, by adding in new ZK-SNARK-friendly precompiles that provide functionality for developers with low prover times and gas costs.

Type 4 (high-level-language equivalent)

A Type 4 system works by taking smart contract source code written in a high-level language (eg. Solidity, Vyper, or some intermediate that both compile to) and compiling that to some language that is explicitly designed to be ZK-SNARK-friendly.

Advantage: very fast prover times

There is a lot of overhead that you can avoid by not ZK-proving all the different parts of each EVM execution step, and starting from the higher-level code directly.

I'm only describing this advantage with one sentence in this post (compared to a big bullet point list below for compatibility-related disadvantages), but that should not be interpreted as a value judgement! Compiling from high-level languages directly really can greatly reduce costs and help decentralization by making it easier to be a prover.

Disadvantage: more incompatibility

A "normal" application written in Vyper or Solidity can be compiled down and it would "just work", but there are some important ways in which very many applications are not "normal":

Developers should be mindful of these issues.

Who's building it?

ZKSync is a Type 4 system, though it may add compatibility for EVM bytecode over time. Nethermind's Warp project is building a compiler from Solidity to Starkware's Cairo, which will turn StarkNet into a de-facto Type 4 system.

The future of ZK-EVM types

The types are not unambiguously "better" or "worse" than other types. Rather, they are different points on the tradeoff space: lower-numbered types are more compatible with existing infrastructure but slower, and higher-numbered types are less compatible with existing infrastructure but faster. In general, it's healthy for the space that all of these types are being explored.

Additionally, ZK-EVM projects can easily start at higher-numbered types and jump to lower-numbered types (or vice versa) over time. For example:

Personally, my hope is that everything becomes Type 1 over time, through a combination of improvements in ZK-EVMs and improvements to Ethereum itself to make it more ZK-SNARK-friendly. In such a future, we would have multiple ZK-EVM implementations which could be used both for ZK rollups and to verify the Ethereum chain itself. Theoretically, there is no need for Ethereum to standardize on a single ZK-EVM implementation for L1 use; different clients could use different proofs, so we continue to benefit from code redundancy.

However, it is going to take quite some time until we get to such a future. In the meantime, we are going to see a lot of innovation in the different paths to scaling Ethereum and Ethereum-based ZK-rollups.